When the Roman nobleman Cassius attempts to persuade Brutus to join the conspiracy against Caesar in Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Julius Caesar, he does so by including a rejection of divine predetermination:

“Men at some time are masters of their fates:

— The Tragedy of Julius Caesar, Act 1, Scene 2

The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars,

But in ourselves…”

His appeal is meant to empower Brutus. Don’t give in to tyranny simply because you think providence has willed it to be thus, Cassius tells him. You have the ability to act!

Caesar, on the other hand, embraces supernatural prediction. He assumes his outlook is rosy because he thinks his destiny is written by an omnipotent, incontestable power. In a fatal twist, he mistakenly interprets an omen in a way that is favorable to himself, and he pays the ultimate price for it. His belief in the authority of fate never allows him to entertain the notion that his destiny could be anything but fixed.

The repudiation of fate is a reoccurring theme in Shakespeare’s plays, as is the idea that one can take charge of one’s own destiny. It is a theme which serves to illustrate the shifting perceptions of the time, away from superstition and towards the belief that human beings have the capacity to shape the course of the world to come.

Today most of us think our intuitions are utterly detached from superstition. We believe our institutions are secular and meritocratic. We respect — even venerate — those whose talent and acumen led them to great heights and accomplishment. Their stories exemplify the power of the individual, after all, as well as the bootstrapping ideal found within the ethos of The American Dream. These laical idols are touted as case studies in human potential, and we scrutinize their characteristics and the choices they made in order to fashion curricula we think will teach us how to achieve similar success. Want to be a great entrepreneur like Steve Jobs, a writer like Hemingway, or an artist like Jeff Koons? Simply Google them and you’ll find countless resources purporting to have the know-how. Contained in these are lessons distilled from the lives of these high-achievers. Best of all, they are delivered in bite-sized chunks of easily digestible step-by-step wisdom. Read them and you’ll have the insight you need to become successful yourself. Uncertainty will all but evaporate! The world will snap into place around you like a well-designed LEGO set! Wonderful!

Sarcasm notwithstanding, the belief that there is a procedural approach to accomplishment is a widely held one. Not convinced? Take into consideration the mind-boggling numbers behind the self-improvement industry, which is projected to reach a market value in the U.S. of nearly $13.2 billion by 2022. If we didn’t believe in the efficacy of all the 5-step, 10-step-, 12-step programs, or tips, tricks, and mind-hacks, we certainly wouldn’t be spending that kind of dough on them. I’m not suggesting self-improvement is bogus. It’s clear that many people have improved the quality of their lives by following rigorous systems which help promote change. Valid and effective systems do exist. The takeaway, rather, is what this undeniable tendency we have of gravitating towards procedure reveals about our nature — and it is this:

Our superstitions still exist. Only now, instead of the divine, our adoration is reserved for process: clear-cut successive steps, blueprints, game plans, things that tell us what to do and when to do it. Process fuels business strategy, political policy, individual resolutions, and even the way in which we interact with each other. Our belief in process shapes the way we approach many of the challenges we face in everyday life, including how best to educate our children, how best to invest our money, and how best to pursue our career. The promise of process is that it will eliminate doubt and ensure a specific outcome. But should we really trust in it?

Luke Anderson is a self-taught artist based out of Salt Lake City, Utah, and his own experience has taught him to be wary of any procedural approach to success.

“Take all career advice with a grain of salt,” he told me. “No two artists found success in the same way. There are so many ways to navigate the art world.”

Originally from Cheyenne, Wyoming, Luke Anderson thought he would be a musician, not a visual artist. But that changed when he discovered, as he put it, “I was better at painting than I was at playing the guitar.”

Despite that revelation, his path towards becoming an artist wasn’t a straight one. “I took two semesters of art at the University of Wyoming before ultimately changing my major,” he told me. “My professional art training is pretty limited.”

Those semesters included classes that provided him a firm grounding in the fundamentals of art, however, including coursework in observational drawing, 2D and 3D design, and color theory. Later, as his longing for creative expression refused to wane, he embarked on a course of study that was entirely self-directed. He taught himself the principles of oil painting through investigation and observation, closely scrutinizing the work of both historical and contemporary artists to glean important lessons. It is a method of learning he still follows to this day. “I try to see as much art as I can in person whenever I have a chance,” Luke said. “And I like to see art from a lot of different genres to expose myself to a wide variety of techniques and concepts.”

“There is a lot of trial and error and failures associated with approaching an art career this way,” he added. “But it is ultimately satisfying to figure things out on your own, even if it takes a little longer.”

While there are some who might question such an approach, citing inefficiencies and possible errors that may arise from the lack of a directed curricula, I would have to disagree. The literature appears to support Luke’s approach to learning. Neuroscientific research in the field of creativity has suggested that the drive for exploration and learning could very well be the most significant personal factor predicting creative achievement. Open engagement, while it may not always have a positive result, triggers mechanisms in the brain associated with idea generation and others that provide fuel for innovation. So while Luke may not have been subjected to the rigors of a formal art education, his personal methodology has set him up for a lifetime of creative accomplishment.

And if you take a look at his record, you’d have to agree he’s well on his way.

One of the first significant juried art shows Luke attempted was the 2017 Wyoming Capitol Governor’s Art Exhibition put on by the Wyoming State Museum. Two of his pieces were accepted and sold during the show. Seeing how his work compared to other more seasoned artists from around the state turned out to be an invaluable experience as well as a confidence-booster. Since that point, he’s participated in a number of other juried shows around the state and racked up awards along the way, including 1st Place ribbons, People’s Choice, and Juror’s Top Scoring Work honors. In 2020 he was also invited to submit work to the Gallery at the National Western Club for an exhibition and sale affiliated with the renowned Coors Western Art Show.

But while his exploratory approach has served his own career well, Luke is still hesitant to dole out authoritative prescriptions to budding artists. “One method that worked for one artist might not work for you,” he said. “Go at your own pace and do what you are comfortable with.”

That wisdom is a far cry from most advice artists are generally subjected to. Want to become an artist? There are many “experts” out there willing to tell you how to make it happen.

Success, according to them, follows a procedure — a process.

In the world of art, we see countless examples of surefire ways to achieve success. Open YouTube and you’ll find a thousand “influencers,” each trumpeting their own “guaranteed” method of attaining creative stardom. Speak with a gallerist and you may get a lecture about the size, color scheme, and subject-matter your art should feature in order to ensure sales. Ask an artist what it takes to build a successful career and you may be given a list of specific shows to attend and people to cozy up to. One could easily think it’s all been figured out — but why, if this is the case, do so many artists still struggle?

The problem is we still believe in fated outcomes. Unlike Julius Caesar, however, who thought his path was illuminated by oracles, our faith is in something we believe to be appreciable, empirical, and based on objective fact: process. It is in it we trust.

Unfortunately, like Caesar, this faith isn’t always rewarded as we think it ought to be. In the world of venture-capitalism, with its process of “unicorn hunting,” this faith may result in hundreds of millions of dollars of investment lost to an idea most outside observers found ridiculous from the get-to. In the world of education, this may result in thousands of children being left behind as they struggle to adapt their learning patterns to those which are not conducive to their unique requirements. In the world of politics, this may result in a leadership process which ignores warnings of impending disaster and allows preparations to be undermined. To be fair, in some cases adherents felt at odds with the process that drove governance, but were held captive by it. In others, however, true-believers were blindsided when something unexpected suddenly blew it all up in their faces. The point is that process — if it enslaves the decision-making chain — can easily lead anyone astray.

The alternative, however, is something that feels uncomfortable to most of us.

In the absence of a clearly-defined process, uncertainty and doubt run rampant, and that can take a toll on self-confidence. Hopelessness can easily set in, and one can question whether or not it is worth continuing. For creative people — those who allow their curiosity and desire for exploration to drive them — it can make things especially difficult.

Luke, for his part, finds that these nagging doubts arise on a daily basis.

“This is a mental obstacle I deal with every time I sit down at my easel to work,” he told me. “It’s a very common problem among artists.”

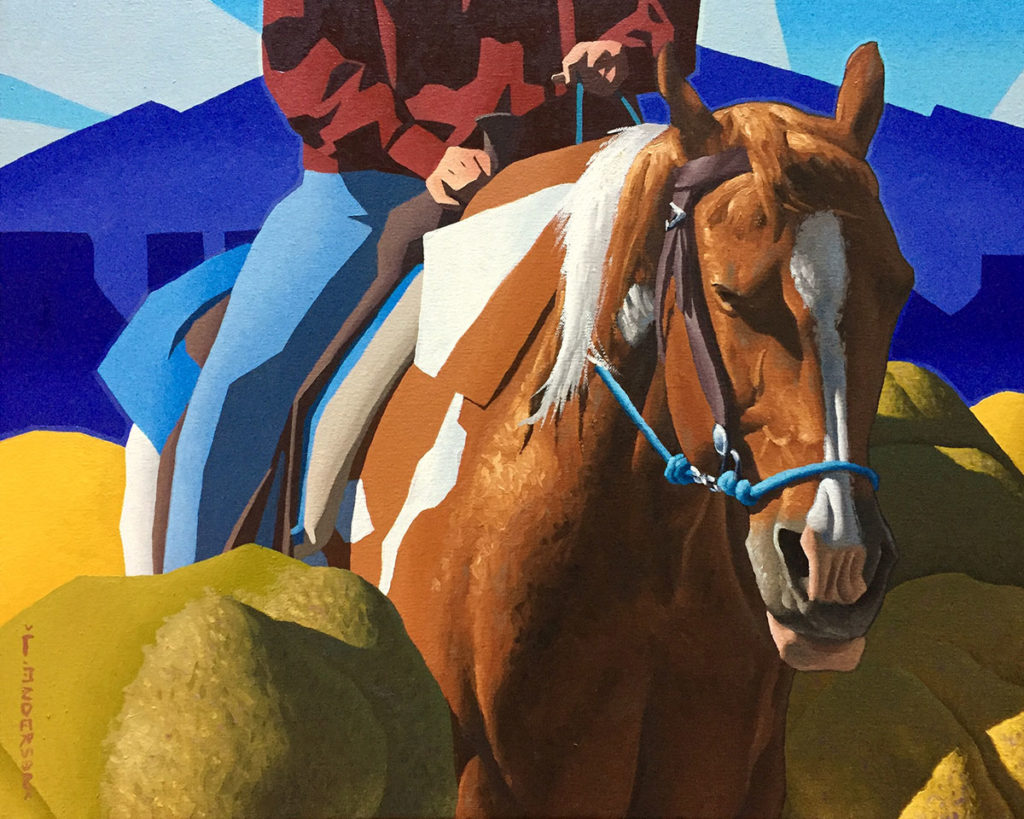

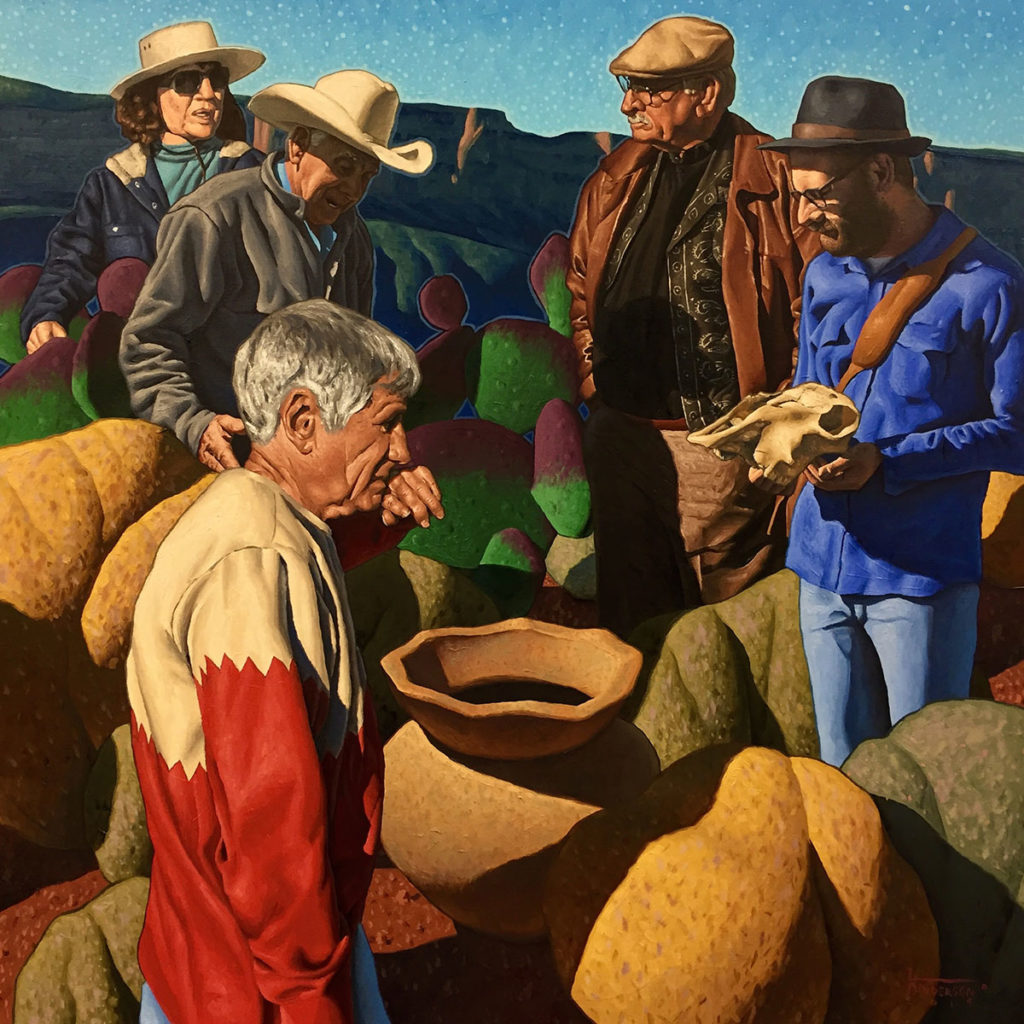

Look at a Luke Anderson painting and you won’t find a hesitant brush stroke. Nor will you find any other sign of ambivalence. His are bold compositions and carefully constructed. They exude a confidence which make them stand out on display. Whatever doubts Luke may have had at approaching the easel appear to have vanished once he began mixing paint.

When you inspect Luke’s work, you see that his subjects have a dimensional quality to them. This is the cumulative effect of color, contrast, and application — all skillfully integrated in a way that plays with the eye. If you reach out with your hand, you think to yourself, you could wrap your fingers around that antelope, that horse, that cactus. While a photograph may be a facsimile of reality, a Luke Anderson painting offers something different: a facsimile of something you wish to be real. The tactile quality, molded appearance, and refined edges seize you, beckon to you to look and look again as a whispering urge to touch each figure winds its way around the back of your mind. You shouldn’t, though — touching is not allowed. So the urge will remain unfulfilled and you will leave with the image burned into your head, and with the impression of having been so close to something while, at the same time, still too far away. It is a contradictory feeling, one of both satisfaction and discontent. That is a good thing, I think, especially for Luke, because it keeps his viewers wanting to come back again and again. His work is alluring.

“I personally don’t feel like an expert in the Western subjects I paint,” Luke told me. “In fact, that’s primarily why I paint them. I grew up in the West, so these subjects fascinate me, but the West is such a bizarre place. I paint these subjects simply because I am trying to understand them, understand how they all fit together, understand how they individually relate to a bigger picture.”

It’s easy to see how this is reflected in his art. It is a persistent inquisitiveness that has taken shape on each of his canvases. In them we can see his drive for exploration, his own curiosity translated through pigment. It seems to speak of limitless possibility and wonder. And through it, as well, we can see his uncertainty subdued — as well as something I would liken to a call-to-action. It is a call other artists can take heart from, an assurance of solidarity in times of adversity, and an encouragement to keep moving forward despite those nagging feelings of doubt.

“We overcome it simply because we know that art is the only thing we can ever see ourselves doing with our lives,” Luke told me. “We overcome because we have no choice but to move on and keep working.”

And that work may take artists unexpected places, down rabbit-holes and dark alleys of interest that may seem unrelated to the business of making art. But that’s okay. In fact, among those who understand how creativity works, it’s expected. As creativity researcher Scott Barry Kaufman and psychology reporter Caroyln Gregoire wrote in their book Wired To Create, “creative people not only cultivate a wide array of attributes but are also able to adapt — even flourish — by making the best of the wide range of traits and skills that they already possess.” (p.xxv)

Exploration, growth, and adaptation are all scientifically observed attributes which set the stage for creative innovation and accomplishment. They also appear to fly in the face of what much of the advice industry appears to believe. To them, stringent procedures and strictly-defined paths are what we must follow to achieve success.

So why the disconnect?

In the psychological literature the tendency for people to use only familiar methods to solve a problem, despite the availability of better ones, is called the Einstellung effect. It is a common state of mind that is made worse when stress is introduced into the mix. Basically, it is a cognitive bias that can easily transform into a disastrous impairment when the heat is turned up. The alternative — employing deep rational thought — isn’t something we readily accept, because we naturally resist spending mental effort on a problem we think we already understand. Our minds, guided by the models we’ve already established, convince us there’s little need to think a little deeper, so we go with the mechanism we already know. We are, in a sense, built to trust in process. But our attraction to process is simply a penchant for the mechanization of cognition.

This boils down to our tendency as humans to seek out efficient cognitive solutions to everyday problems so we can dedicate precious processing power to other, more demanding, issues.

Undoubtedly, this ability to fashion heuristic mental procedures is one of the reasons our species has advanced at the incredible rate it has. It’s among our most useful abilities. In fact, it has proven so valuable over the years that it has effectively been baked into our genetic makeup from a lengthy bout of natural selection. There’s no question it’s handy to have in our mental toolkit, but it also has a way of getting us into trouble. It is how our prejudices are formed, how we fall into the rhythms that form bad habits, and how we unconsciously make any number of poor decisions in our daily lives despite available evidence that tells us to act differently.

This means we’re vulnerable. The certainty we feel about any given thing is mostly an illusion of our own making. So, really, we’re flying blind without realizing it. The immense shock we feel when something doesn’t go the way we were convinced it should have is an excellent indication of this phenomena. In moments like these, the process through which we understand the world is shown to be flawed, but do we take note of it? Do we learn? Some revise their notions after this type of experience, but most of us don’t. We continue to walk around with an incomplete, skewed, or illogical awareness of the realities surrounding us — all because our minds are more comfortable existing within the paradigms they have worked so hard to create.

But what does that mean for the processes we’ve fashioned? The blueprints, game plans, and 12-step programs?

Consider that most of us fall victim to our own biases, unreason, and irrationality on a daily basis, and ask yourself this: can a flawed cognitive system actually construct a process that won’t reflect those same problems?

The answer is no, and proof of this can be found all around us. Take, for example, the algorithms we’ve developed to assist in fields like insurance, education, and policing. Many of these have been shown to hold the unconscious biases of their makers. At first glance this may not seem like a big deal, but when we consider the ways in which many of these algorithms are used today and the scale at which they’re used, we can see how these flaws would easily exacerbate problems such as inequality at an exponential rate in a system-wide manner. An inherently flawed process is a disaster waiting to happen, and these days, in our super-connected world, that disaster can cascade at a pace and at breadth that’s hard to fathom. The process we create to help ease our load can easily turn the tables and cause untold harm on us and those around us.

The solution here is we must accept that process, in it’s many forms, will always be flawed, and we must be prepared to challenge it. In other words, we must learn to take it with a grain of salt.

It would be wise to learn from the example of Luke Anderson, and allow our drive for exploration, discovery, and knowledge to guide us. This may seem messy, it may involve a lot of trial and error, but it’s the kind of methodology that is more likely to be meaningful and more likely to achieve innovative results. Don’t be fooled into thinking a procedural approach to success exists.

The illusion of certainty should not be mistaken for truth. Life is a messy business, and if we want to live it to the utmost, it’s important that we accept it for what it is. And that means we need to become comfortable with ambiguity, with the unknown and with the opaque. We must learn to adapt, to revise our efforts to better suit each new situation, and explore new possibilities. True, this is not an easy thing.

While Shakespeare may have had much to say on the subject of fate in light of the changing perceptions of his time, I’m not sure his plays would have changed much had they been written in this modern era. We are still very much bound by the notion of predetermination, although the “stars” to which the Bard referred in The Tragedy of Julius Caesar would likely mean something other than the divine in this day and age. Today, he very well might have written those famous lines in regard to our modern sense of fated outcomes: our beloved process and procedure. And even then, his point would still hold true. Don’t give in to a vision of the future that is not your own, simply because you think the path has been preordained. You have the ability to act!

Luke Anderson’s work can be found at Deselms Fine Art in Cheyenne, Wyoming, his website and on Instagram.

Support Regional Arts Coverage!

The Featured Artist article series was conceived as a way to showcase the stories of artists and creative people residing in the regional West while contributing to a wider conversation about creativity and the world of art.

To ensure this work continues, please consider supporting it.

Your contribution provides vital assistance and serves to demonstrate your appreciation for the work regional artists and creative people do to keep our communities vibrant and full of imaginative light.

If you enjoyed this arts coverage, donate below to keep the content coming! Learn more about becoming a supporter.

To be featured in an upcoming Featured Artist article, or to nominate someone, please Contact Me.

Nick Thornburg is a multidisciplinary artist and writer. Follow Nick and share the work on social media. Subscribe to his mailing list to keep up-to-date with upcoming features and other news.

Stay Creative.