It was late in the afternoon on a brisk February day in Lander, Wyoming, and my hands were full of art supplies. I stood at the door of Sweetwater Studio, looking at the antler-shaped handle, a collapsible easel in my left hand, a portfolio heavy with drawing paper in my right. A full-to-the-brim messenger bag was slung over my shoulder. Getting the door open became a puzzle as I shifted my load precariously over to one hand in order to free the other. I had no intention of letting my things touch the salt-strewn sidewalk, and I made good on that commitment by throwing open the door, rushing into the studio, and quickly reorienting myself before anything fell. As I stood just inside, allowing my eyes to adjust to the light, the grinning visage of Jenny Reeves Johnson slowly took shape in front of me.

It was the first time we had met in person.

Jenny is a person of exceptional energy, with visible passion, the source of which is clearly her love of craft. When I met her on that day in February, I couldn’t help but feel comforted, knowing I’d come to the right place, knowing that I’d met a kindred spirit. She had organized a reoccurring figure drawing session for a small group of local artists, recruiting models from the area and scheduling them to sit for three-hour sessions. Upon entering Sweetwater Studio it became obvious to me Jenny knew exactly what she was doing — this was not her first rodeo. The more I came to learn about her, the more I came to understand her professionalism and experience should not have been unexpected on my part. Jenny Reeves Johnson’s list of accomplishments in the arts is long.

Don’t ever quit. If you carry that passion, keep it alive.

— Jenny Reeves Johnson

After earning a degree in Art from the University of Tulsa in Oklahoma, Jenny maintained a studio practice along with a number of teaching positions, including one as an art educator on the Wind River Reservation, and a career managing ranches alongside her husband and daughter. Over the years she also kept to a steady diet of self-directed skill development. “I grabbed every opportunity to keep moving forward with my art,” she told me. “I am still seeking those opportunities.” This dedication to learning can clearly be seen, not only in the range of work she produces — from oil paintings, to pastel illustrations and highly-detailed and intricately constructed works in clay — but in the power of her work, reflected in the range her shown and collected pieces enjoy. Jenny’s work is displayed in collections throughout the country, is represented in Santa Fe and Jackson, WY, and makes regular appearances at the renowned Brinton Museum on the historic Quarter Circle A Ranch in the foothills of the Bighorn Mountains. The credits to her name go on.

Yet, out of all her years of experiences, one of her most cherished memories comes from early in her career as an artist. “I was asked to paint portraits of the oldest living Arapaho elders,” Jenny said. “I was right out of college in my first art teaching job. They respected my ability enough to ask me this important cultural task.” 44 years later, she looks back upon that undertaking and understands how powerful it really was. “I realize the epic event it was in my art development,” she said. The two pieces she created still hang in the school even to this day.

Sweetwater Studio is housed in a red brick building along the main drag in Lander. Its interior is narrow, with high ceilings and walls whose character you wish you could decipher, like hieroglyphics, to learn the history they’ve borne witness to. Bright, varied paintings are on display, awaiting the visitors who are free to come and meet the artists who share the space with Jenny. Bronze statues sit in the window, beautifully patinaed, and greet you just inside the door. It is a gallery, a gathering place, and a workspace all in one, a fitting example of the collaborative and inclusive environment Jenny seems drawn to — or seeks to build.

During that February figure drawing session where we first met, she took the lead, but kept to what I came to know as her characteristic accommodating demeanor. Lights. Space. Pose. Timing. Music. She guided the session with the grace and conscientiousness commonly found in experienced educators, always keeping to the schedule while maintaining a comfortable environment. My charcoal pencil flowed effortlessly across the page, and once the session ended I knew I wanted to return. Set and setting is vital to the creative act, and Jenny knew just how to create the proper space for it.

And so I promised myself I would come back.

Get out there and make some stories so you will have something to say. — Jenny Reeves Johnson

Over time I came to learn that Jenny shared my interest in narrative and the ways in which art can be a powerful storytelling device, revealing hidden truths about the world in which we live. She hopes to leave a legacy of art that will “tell timely stories of what our world is,” as well as “the good parts that we have to work to keep.” She recognizes this isn’t an easy task, and one that many young creators frequently become overwhelmed by. How do I find my voice? What do I have to say? Is what I’m saying worthwhile? Instead of diving headlong into the heady work of answering those questions right out of the gate, Jenny advises artists to concentrate on living life and gaining experience. “Get out there and make some stories so you will have something to say,” she says. She also warns against the danger of becoming distracted by starry visions of massive studios, magazine covers, and world acclaim. This can easily become a trap, leading an artist away from that which is necessary, which to Jenny is “getting salty, living a life to have stories to tell.”

To illustrate this commitment towards allowing lived experience to inform the artistic endeavor, and giving that work license to speak towards those universal things which transcend the individual, Jenny shared a story. In 2007, the health of a 32 year old mare, who Jenny had owned since the horse was 18 months old, began to fail. Jenny realized she needed to do something about the anxiety she felt.

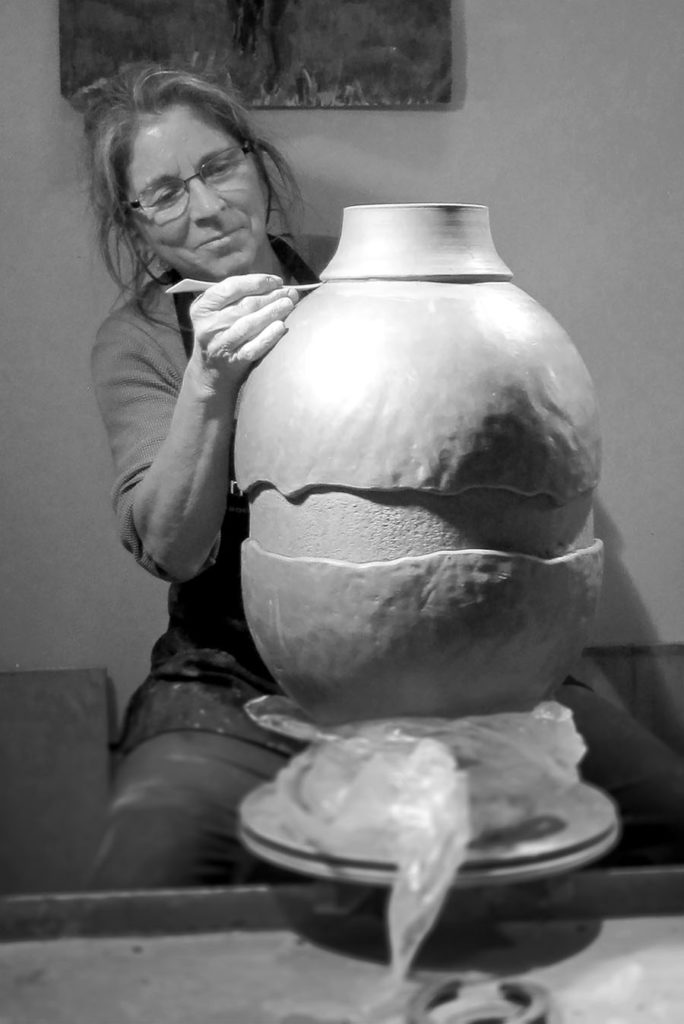

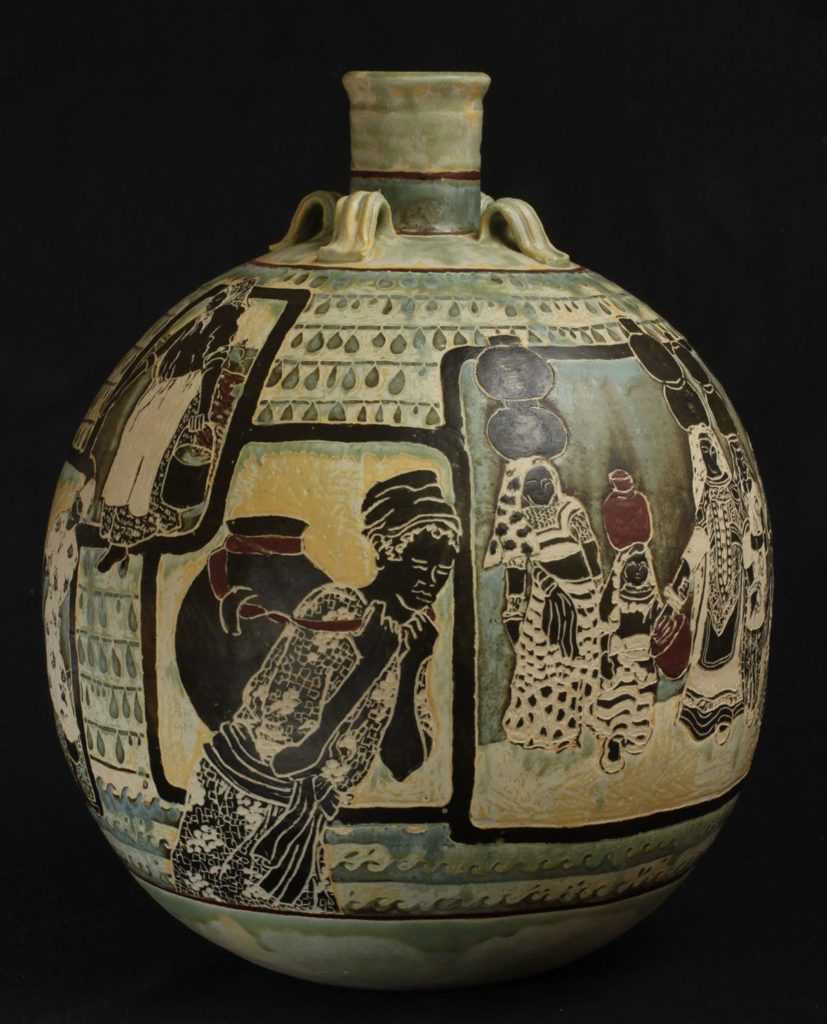

“I decided to create a large pot and put her image on in. On the other side of the flattened round shape I composed all the horses we had during her life that were a part of ‘our family’. After her passing I placed some of her mane and tail hair inside the large vessel. That began a direction for me documenting important stories on clay vessels,” Jenny said. “I found myself developing vessel after vessel documenting important parts of myself. My daughter, my horses, dogs, bison, the western landscape, wildlife, and the human experience became my subject matter.”

Later, while visiting a museum in the San Francisco area, she came across an exhibit of old African art. “I connected with the very primitive basic representation of a long ago human world, all of it in clay and stone — a little wood. In a that moment, I was standing next to a human’s hand speaking powerfully to me and I felt the presence of this human. This artist had no signature and it [was] laughable how unimportant that was. It was about the ancient human experience.”

“I saw my art in a new perspective,” Jenny said. “The real worth comes from the power [the work] carries as it leads its independent life [and its message] through time.”

Figure drawing is the drawing of a human subject, and in traditional practice that means drawing from life — rather, using a live model. Sessions typically begin with the model taking several quick poses, only a few minutes in length, while the artist creates what is known as a gesture drawing. Artists generally use gesture drawings to warm-up, seeking to capture the major forms, movement and feel of the model in broad, expressive strokes (this does not mean, however, gesture drawings cannot be beautiful — many artists create spectacular gesture drawings worthy of display).

The model then begins to hold incrementally longer poses, culminating in a pose that can last an hour or more. Widening the time margin allow artists to work on increasingly polished drawings by focusing on the details of anatomy, lighting, and composition. Time constraints and the variety of poses force artists out of their comfort zone, challenging their abilities of observation, their knowledge of proportion, and their capacity to efficiently and effectively wield a pencil, brush, or charcoal stick. On a bad day the experience can dissolve into a wicked mess. If an artist is distracted, unfocused, feeling unprepared or unwell, frustration can easily set in. I’ve known many artists who avoid figure drawing because it is so difficult, and because they’d rather avoid the frustration of poor performances. I’ve known others who avoid it because they hate drawing with the added pressure of performing in front of their peers. In order to make the best of a figure drawing experience, it is essential that the environment remain collected and calm, and that it provides a comfortable space for all involved. This is not as easy as it may seem — deliberate choices must be made to cultivate that specific kind of habitat to get the best creative work out of all participants.

The sessions at Sweetwater Studio were exactly that.

I believe in everything I put out there. What I say will be around. That is how I think. — Jenny Reeves Johnson

Jenny Reeves Johnson is a person who understands how sensitive the creative process can be. I was able to see that capacity in her from the very start. She made the effort to fashion an environment where we could all strive to do our best work — where the challenge was balanced precisely, to a point where we wouldn’t be pushed too far beyond our abilities, risking frustration, and where the supportive nature of the group kept ugly competitiveness and performance anxiety at bay. If I had to guess, this effort to accommodate and do right by the creative needs of others stems from a sort of professional empathy in Jenny, a deep-rooted understanding of what it feels like to live a life in a creative industry. She understands the anxiety artists feel, the fear of putting hard-won work out into the world and having it degraded, dismissed, or ignored. She understands the pain of artists’ rejection. She understands how artists can come to question the worth of their own work even after a single callous observation or a poor judgment at a show.

“I don’t handle judged art shows very well,” she shared with me. “I can feel great about my work and then if judging does not recognize it I feel pretty shaky about my own opinion and worth. I start doubting myself. All that lasts for a very short time because I know intellectually how subjective it all is. I move on but keep those insecure feelings filed away in a deal-with-it-later folder.”

Being an artist can be grating on the emotions. Jenny understands that. But she continues to move forward. And this effort carries over to her wider creative community. She wants everyone to fulfill their creative dreams. “Don’t ever quit,” she said. “If you carry that passion, keep it alive. Even if you are married, having children, managing a ranch, training and showing stock dogs, horses, fighting for conservation issues, teaching school, staying in shape, shopping and cooking for a family and ranch staff, don’t quit finding time for your art interest and development.”

In this day and age it can seem almost impossible to live a creative life, or to become an artist. There are a couple of overarching reasons for this. Celebrity culture and the cult of personality serve to obfuscate the real work most creators put into their craft. Like the wizard who fooled the citizens of Oz with theatrics and distraction, these myths obscure real human stories and indoctrinate generations of would-be artists into a dangerous philosophy that values acclaim above all else. The outcome of this is a story that seems to advocate the idea that if an artist doesn’t enjoy something like a huge following on social media, she probably isn’t doing worthwhile work.

Alongside another modern narrative, which supports rapid wealth accumulation and cut-throat commercialism (and deifies the few who succeed while practicing this creed), the result to the arts is devastation. Success is seen as a pie of limited size, and a larger slice for one person means a lesser one for another. Many of those who wish to live more creative lives feel they cannot do so. Even if they are able to make space for creative work in their busy lives (one of the largest barriers) the idea they will have to compete, to fight to get their work in front of an audience becomes an insurmountable hurdle.

It is especially discouraging when these would-be creators inevitably compare themselves to the larger-than-life, god-like brands of those they admire — those who’ve made it. The industry — and the wider culture — suffers because of the cyclical pattern that arises out of this: those who enjoy a large platform increasingly grow that platform — the momentum and sheer bulk of their presence pushes aside those who would add their voice to the conversation, or discourages them from joining in the first place out of a sense of predetermined failure, thus allowing those with a large platform to continue to grow it unabated. The outcome is a smaller, less diverse, more narrow-minded conversation which, by its very nature, discourages innovation, development, and overall growth.

But Jenny Reeves Johnson is someone who exemplifies what it means to be an artist. She strives to maintain authenticity in her work, to avoid the influence of glossy visions and trends that sidetrack so many artists. She recognizes the difference between what it is she can do, and what it is she should. She understands what is popular in the moment is usually fleeting, an ephemeral thing creators can never really catch up to, and she doesn’t allow it to change what it is she knows she should say with her work. “I like my voice,” she said simply.

Given the fact her clay pieces could very well last thousands of years, I think it’s safe to say the echo of her voice will reverberate for a very, very long time.

“I believe in everything I put out there,” Jenny said. “What I say will be around. That is how I think.”

It was dark when the life drawing session at Sweetwater Studio came to an end. As the group packed up, I shuffled through my drawings, taking mental notes on points where I needed to improve. Then I slipped them into my portfolio and collapsed my easel. It’s easy for artists to be overly critical of the work they do, to feel discouraged about their skill-set or progress, but that February night I felt none of that. I said my goodbyes and was seen out with an encouraging wave and smile from Jenny. I carefully made my way out the door with my load and paused on the sidewalk. It was quiet, and the stars were out, blanketing the night sky like jewels strewn across an endless dark sheet. They sat there, as if waiting to be collected.

I made my way home, believing a life full of creative possibilities lay ahead of me.

Inside of me, a white-hot feeling of faith — in myself, in the creative process, and in the value of the life I was living — burned like an eternal flame.

Don’t ever quit.

Don’t ever quit.

Ever.

Jenny Reeves Johnson’s work can be found at Gerald Peters Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico; Trailside Gallery, Jackson, Wyoming; the Yearly Small Works early winter show at the Brinton Museum, Big Horn, Wyoming; Cowboy Coffee, Jackson Wyoming, Dec 2020; and Sweetwater Studio, 232 Main, Lander, Wyoming.

Support Regional Arts Coverage!

The Featured Artist article series was conceived as a way to showcase the stories of artists and creative people residing in the regional West while contributing to a wider conversation about creativity and the world of art.

To ensure this work continues, please consider supporting it.

Your contribution provides vital assistance and serves to demonstrate your appreciation for the work regional artists and creative people do to keep our communities vibrant and full of imaginative light.

If you enjoyed this arts coverage, donate below to keep the content coming! Learn more about becoming a supporter.

To be featured in an upcoming Featured Artist article, or to nominate someone, please Contact Me.

Nick Thornburg is a multidisciplinary artist and writer. Follow Nick and share the work on social media. Subscribe to his mailing list to keep up-to-date with upcoming features and other news.

Stay Creative.